Imagery Support to Disaster Relief OrganizationsTable of Content

About the Case StudySupplying value-added, space-based imagery to disaster relief organizations became an significant part of the work done by Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) in the aftermath of The Great Sumatra-Andaman Earthquake and Indian Ocean Tsunami, which struck on December 26, 2004, killing at least 225,000 people in 11 countries. PDC damage assessment analysts could see that “everything was destroyed” from their position on the ground, but that didn’t tell them or others what they needed to know in order to plan, direct and provide the most effective response, and to make the best-informed decisions about the movement of personnel and resources.

PDC maintains close working relationships with many satellite imagery producers, including commercial companies, international organizations and agencies of the U.S. government and foreign nations. When disaster strikes, images from many sources may be analyzed together to provide the best possible support to disaster managers and relief organizations. (Illustration: PDC)

PDC Imagery Analyst Rich Nezelek: “During the week immediately following the IO tsunami, satellite imagery vendors Digital Globe and Space Imaging decided to openly share their datasets to assist in the humanitarian response effort. PDC started receiving this imagery via our NGA Sky Media (National Geospatial Intelligence Agency) station and we quickly realized that the small work station was not equipped to handle the size and scope of this event. Since this was coming to a head on New Year’s Eve, we scrambled to upgrade the storage capacity and other hardware to accommodate the huge surge of data being pushed through. All together, we ended up with over 1.5 Terabytes of imagery covering a huge area of the Indian Ocean. The next step during the response was to process the images and provide it to the people in the field who needed it— including some of our own staff providing support in Thailand and Indonesia. Connectivity was a major concern for many of the responders, so we utilized compression techniques to make the datasets more manageable. Once we had the final scene knocked down from one or two Gigabytes to around 50 Megabytes, we put them on a publicly accessible (password protected) website. We were among the first to provide this type of support for the event and it proved to be a valuable service to many agencies and governments.” How does space-based imagery help?The usefulness of remotely sensed (RS) data such as satellite-based imagery of threatened or impacted terrain is incalculable. By having a clear photo-like depiction of, for instance, an area that is currently threatened by wildfire, it is possible to know what critical infrastructure is at risk and how to approach the task of fighting the fire: Where are the essential power supplies and their delivery lines? Is the roadway that is in the path of the fire the only way in or out? Are there streams or ponds? Where are there expanses of land with no fire fuels on them? Are there homes in the possible paths of the fire? If so, in which directions? There is no need to send firefighters to defend empty, desert acreage where the fire will go out for lack of fuel. It is urgent, on the other hand, to do everything possible to preserve lives, homes and basic infrastructure. Having recent imagery of a sufficiently high resolution means that responding organizations can make the best decisions about where and how to do their job.

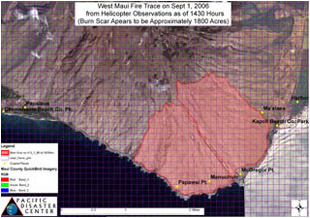

Firefighters battling the West Maui Wildfire of September 2006, left, used

“fire trace maps,” right, based on helicopter photographs shot by a PDC analyst.

Several maps, displaying the aerial (helicopter) imagery on a space-based shot

of the affected area were delivered by PDC during this particular emergency.

Just as RS imagery can help during an emergency, post-event imagery can be priceless in guiding disaster managers, decision makers and relief providers with essential information. Naturally, the imagery maps can show where the terrain or the human-built environment is disturbed, i.e. changed from what is seen in pre-event images, but it can show and clarify much more than that. Carefully analyzed imagery can reveal good news. An image collected immediately following a flood, for example, may show villages along the banks of a river missing. Three days later, new imagery may reveal tents and temporary shelters. This discovery could alert relief workers to change the type of aid they are providing or the priority given to the area. In the aftermath of a storm, a skilled analyst often can discern a wide range of important facts. In addition to identifying where a fleeing population has taken refuge, the analyst can determine what parts of the affected area are at risk of being inundated by retained flood waters or possible landslides, and even whether the most pressing need in an area is likely to be rescue, recovery or basic human necessities like food and water. The imagery might also be needed to discover alternate access routes to be traveled by relief workers when a main transportation artery has been destroyed or interrupted. Aerial pictures (often taken by PDC staff) and satellite imagery (acquired by PDC through longstanding relationships with commercial companies and U.S. and international agencies with satellites) can be like a map, but with a great deal more information. A map is lines-for-roads, imagery can show every streambed, even if local residents have forgotten there was ever a stream; every home and private road; every field and whether it is covered in hay (a fuel in some circumstances, a firebreak in others), another kind of vegetation or none at all. Overhead images—whether space based or taken from airplanes—make it possible to see the gulches and peaks, fields and fuels mix of a given terrain. The uses of RS imagery in connection with wildfire, a storm or tsunami, a flooding event or high wind are similar. PDC Chief Information Officer Chris Chiesa: “PDC is in a unique position to support disaster managers and decision makers with value-added imagery. We have the skilled experts, the technical ability, and also the proven relationships with National Geospatial Intelligence Agency and others who produce imagery through remote sensing—as well as with the U.N. Office of Outer Space Affairs, the U.S. Geological Survey, the International Charter “Space and Major Disaster”—and with the end users of imagery, those who provide relief services, like the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, World Food Program, and others.” The usefulness of the imagery PDC provides depends on the Center’s analysts who use various methods of identifying objects and districts in relation to the needs of the user. Pre-disaster event imagery may show buildings that no longer appear in post-disaster images. A PDC analyst might identify which were homes, commercial buildings or critical infrastructure, such as hospitals, fire and police stations, or evacuation sites. In a worse case scenario—as in the case of Burma in the wake of Tropical Cyclone Nargis—perhaps an analyst may indicate an entire village is missing. PDC Chief Information Officer Chris Chiesa: “Imagery analysts are working with conditions a lot more demanding than the ones you encounter when you search for your own home on Google maps. Also, they often need to know not just what an object on the map should look like, but what it is for. This is a large building, but is it a hospital, for example. And they are frequently called on to determine, by comparing various images or referring to other data sets, what something means. For instance, if there are acres of water here, was it here before? Does it belong here? Are farmers irrigating rice paddies or losing crops to floods?” Often, one value of RS images is that they already exist in reliable, searchable archives. On any given day, as seen from an airplane or satellite, much of the earth is obscured by cloud cover or haze. So, even though satellites are always capable of transmitting new imagery, the only way to be sure of having clear, sufficiently cloud-free images with the infrastructure, human dwellings, farming, waterways, etc. all visible—as baseline imagery—is to have archives of processed (or ready to process) images. Processed images may be mosaics—“tiles” of cloudless images (from various days) pieced together like a jigsaw puzzle—and they may include many layers of visualized information, as well as metadata (information about the information) that can be essential to analyzing the image and interpreting it for relief workers. PDC is sometimes called on to manage projects when The International Charter “Space and Major Disasters” is activated in response to a call from a relief agency for space-based imagery. The Charter, begun in November 2000, is a way for disaster-response organizations around the world to coordinate activities associated with acquiring, interpreting and using space-sourced data on disaster events. PDC’s assignment, as project manager, is to locate the best available images of the disaster area, process them as necessary, and provide them to the agencies planning and performing the relief work. The images must be understandable, of a scale and resolution that provides the needed information, and in a form or medium useful in the circumstances. Giant images transmitted by e-mail, for example will often not work. Large files placed on a website may work in more situations. However, in disaster situations, the World Wide Web, not to mention electricity or even a computer, may be out of reach. Paper prints, a laptop, a plug-in hard drive and other media have all been used by PDC analysts to deliver needed imagery. Cyclone Nargis: Myanmar 2008PDC’s first statement to the general public about Cyclone Nargis, composed by Senior Weather Specialist Glenn James: “Tropical cyclone 01B began in the north Indian Ocean April 27, as a quickly strengthening tropical storm named Nargis. The next day it strengthened into a full cyclone, with 65 knot winds (75 mph). Nargis had a long track, taking it towards India’s east coast, before taking a tight right turn. This new direction took the storm briefly towards the Calcutta, on the Indian coast. A further swing to the right, the east, finally took it towards the west coast of Myanmar. As 01B got closer to the coast, it became clear that this was going to be a very dangerous storm, taking aim at the highly populated southern coastal areas, near the Mouths of Ayeyarwady. This river delta has extremely low elevations, which is unfortunately where the storm made landfall. Devastating winds, along with pounding high surf, and a large storm surge attacked the local population. The storm’s enormous cloud shield brought very heavy rainfall and crippling floods, which made escape from the affected area virtually impossible. As the cyclone made its way further inland, the winds quickly lessened, but the severe rainfall caused flash flooding and mudslides far into interior sections of Myanmar and all the way into Thailand.”

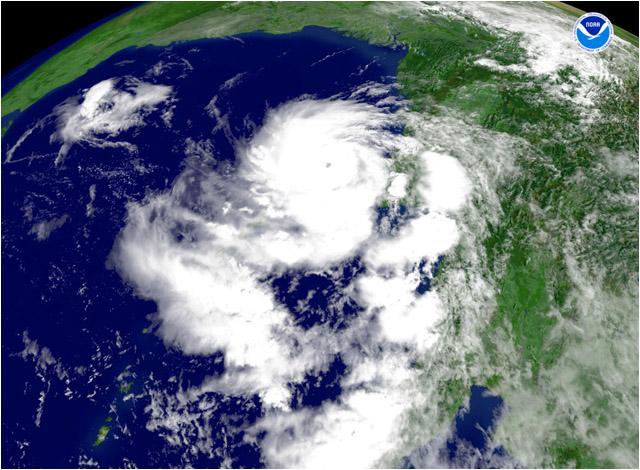

Tropical Cyclone Nargis as seen in a relatively wide-angle, space-based image on May 2, 2008.

The “center-point” of the storm, at this moment, was latitude 14:18:28N and longitude

95:05:24E—off the coast of Burma (Myanmar). Within hours, Nargis killed or fatally

injured at least 132,000 people and caused damage said to be in excess of $10 billion,

although neither number is completely certain. (Image: NOAA)

Twelve weeks later, in an Associated Press story in USA Today, the government of Burma reported that 84,537 people were killed in the initial impact of the storm and that, even then, an additional 53,836 were categorized as missing. Immediately after Cyclone Nargis swept through Burma (Myanmar), international relief organizations found that they were unable to reach affected populations with food, medical supplies, damage assessment teams, heavy equipment and the remainder of the usual response to a major disaster. Hoping, hour-by-hour, for the way to be cleared for full-scale relief, U.S., Thai, Australian and United Nations agencies began staging staff and donations in Bangkok, Thailand. Pacific Disaster Center dispatched Senior Geospatial Data Analyst Todd Bosse to Bangkok, as well. The PDC analyst was in Thailand to assist with relief efforts related to Cyclone Nargis in any way he could, and to coordinate and facilitate communication between the U.S. Pacific Command’s (PACOM) Joint Task Force and various U.N. organizations. His main responsibilities were 1) to gather and distribute before- and after-Nargis satellite imagery for damage assessments, much of which was channeled to him by Imagery Analyst Rich Nezelek from PDC’s Maui headquarters, 2) to serve as a liaison between U.S. efforts (Multinational Planning and Augmentation Team Liaison Office, MPAT LNO) and U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and between various U.N. organizations (OCHA, World Food Program, etc.) with regard to geospatial information and imagery activities, and 3) to provide any and all other geospatial information systems (GIS) support required. Bosse remained in Bangkok for three weeks, continuing to facilitate interagency communications and to be the liaison between the United Nations Initiative Providing Satellite Imagery for Humanitarian Aid (UNOSAT), which was the project manager for the activation of the International Charter “Space and Major Disasters,” and PDC, where the imagery was being processed.

Imagery Analyst Rich Nezelek: “In the six years that have passed since the IO tsunami, the proliferation of high resolution satellite imagery is astounding. While there was very little imagery readily available in 2001 (for the Indian Ocean region), there was complete coverage of Myanmar already processed and available to agencies responding to the damage caused by Cyclone Nargis. Since this pre-event imagery was already ‘in the can,’ we focused our efforts on processing post-event scenes. These were passed on to our analyst in the field who was collaborating with the U.N. to provide damage assessment maps. Many of these maps were also used for the International Charter activation.” Note: Some of the post-event, PDC-processed imagery used by UNOSAT, manager for the International Charter activation, to make the maps everyone used can be viewed on the websites of the International Charter, UNOSAT and PDC. Acquiring, processing, analyzing, distributing and using imagery for humanitarian assistance is always a team effort. You may click on any of the thumbnail insets on the UNOSAT index map below to see an example of a finished imagery-map product used in response to Cyclone Nargis. In the lower left corner of each map, you will see a list of the organizations that collaborated in the making of that one product. Each organization name or acronym likely represents a dedicated team of professionals, as well. Related PDC Resources

Pertinent External Resources

Some links may become inactive over time. If you find a broken or inoperative link

to an external resource, you may want to search at that resource for the relevant

information. If you find that a link referring to a pdc.org page fails, please inform

the PDC Webmaster.

|